Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Is Really Wheat Intolerance Syndrome

“In recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in “non-celiac gluten sensitivity” (NGCS), first described in 1978 (1). This concept now applies to patients who do not meet the criteria for celiac disease (CD) or wheat allergy, but who do report a number of intestinal and/or extra-intestinal symptoms after consuming gluten-containing foods. These patients by definition present neither the autoantibodies nor the enteropathy characteristic of CD.” November 2015 – Stefano Guandalini in Impact, a publication of the University of Chicago Disease Centre

“In recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in “non-celiac gluten sensitivity” (NGCS), first described in 1978 (1). This concept now applies to patients who do not meet the criteria for celiac disease (CD) or wheat allergy, but who do report a number of intestinal and/or extra-intestinal symptoms after consuming gluten-containing foods. These patients by definition present neither the autoantibodies nor the enteropathy characteristic of CD.” November 2015 – Stefano Guandalini in Impact, a publication of the University of Chicago Disease Centre

But is it really gluten that causes NCGS?

“It is important to note that even after a double blind placebo-controlled (DBPC) challenge, there is no proof that gluten is responsible for symptoms. Such challenges commonly use wheat, rather than chemically purified gluten. Thus, it is certainly possible that patients thought to have NCGS may be reacting to components of wheat that have nothing to do with gluten. Other troublesome components of wheat may include, but are not limited to:

- Starch and other carbohydrates such as Fructans (the most common FODMAP contained in wheat) (2);

- Amylase/Trypsin Inhibitors (ATI) – These low molecular weight proteins are found in many modern as well as ancient wheat cultivars and have been found in laboratory systems to cause intestinal inflammation. Thus, it is conceivable, though at the moment only speculative, that they are responsible for some wheat-related gastrointestinal symptoms.

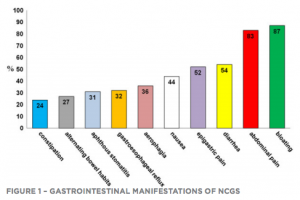

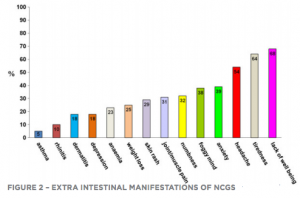

In a survey conducted in Italy on 486 patients with suspected NCGS (3), the clinical picture was characterized by combined gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms (See Figures 1 and 2).

In a survey conducted in Italy on 486 patients with suspected NCGS (3), the clinical picture was characterized by combined gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms (See Figures 1 and 2).

The most common gastrointestinal manifestations were bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhea and/or constipation, nausea, and gastro-esophageal reflux. Among the most common nongastrointestinal manifestations were fatigue, headache, ‘foggy mind,’ fibromyalgia-like joint/muscle pain, leg or arm numbness, dermatitis or skin rash, depression, anxiety, and anemia. In this study, 95% of patients reported symptoms almost every time they ingested gluten.

In another trial, which included 34 glutenfree patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)(4) but no CD, intestinal symptoms and fatigue reappeared more frequently upon reintroduction of gluten than in the control group (68% and 40% respectively).

In another trial, which included 34 glutenfree patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)(4) but no CD, intestinal symptoms and fatigue reappeared more frequently upon reintroduction of gluten than in the control group (68% and 40% respectively).

Additional extraintestinal clinical manifestations described include neurological disorders such as attention deficit and hyperactivity, sleep problems, cerebellar ataxia, psychiatric disorders such as autism, depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, muscular problems and even autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis.

How common is NCGS?

Given the lack of objective diagnostic criteria, it is impossible to say. As a result, estimates range widely, from 0.6% to a whopping 50% on some popular but likely inaccurate websites. NCGS appears to be more prevalent in women than men, in first degree relatives of celiac patients, and in adults rather than children. In fact, there is only limited evidence of its existence in children. (5, 6)

Diagnosing NCGS

In spite of uncertainties about the exact definition of NCGS, the following diagnostic criteria have been proposed:

- Exclusion of celiac disease;

- Exclusion of wheat allergy;

- Rapid onset of intestinal and extra-intestinal symptoms from gluten-containing foods in patients with histopathology as follows: either normal intestinal mucosa or “lymphocytic enteritis” (defined as an increase in the number of intraepithelial lymphocytes in an otherwise completely normal mucosa).

It is essential to rule out CD before labeling a patient with NCGS.

In fact, patients who begin a GFD prior to an adequate diagnostic work-up for celiac disease risk a missed or at least delayed celiac diagnosis. Individuals who believe they are affected by a gluten-related disorder should be screened for celiac disease, which will include a blood test and in most cases an intestinal biopsy while still on a gluten-containing diet.

It has been reported that about 60% of patients with NCGS have a completely normal mucosa. The remaining 40% may have “lymphocytic enteritis”, which is also common in a number of other conditions besides celiac: intestinal infections, H. pylori gastritis, NSAID use, recurrent abdominal pain, common variable immunodeficiency, etc. Still, “lymphocytic enteritis” is part of the spectrum of CD and it is important to differentiate between CD and NCGS in patients who present it. No biomarkers for NCGS have been identified to date; however, positive anti-gliadin antibodies, mainly IgG, have been found in between 25% and 56% of NCGS cases.

This prevalence, although lower than in CD (around 85%), is clearly higher than in the healthy population (up to about 10%) but only marginally higher than what is found with other disorders such as IBS (20%) or autoimmune hepatitis (21.5%). Caution: it is not clear whether these antibodies have any pathogenetic significance, and certainly, given their substantial overlap with controls and with other disorders, their diagnostic value is minimal.

There are no genetic assets known in NCGS: in fact, HLA-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8 genotypes (present in 100% of CD patients) are positive in about 40% of NCGS patients. Thus, genetic testing for HLA haplotypes is not useful for diagnostic purposes.

Gluten challenge for NCGS diagnosis

Because there is no specific biomarker for NCGS, the only reliable standard for diagnosis would be a double blind, placebo-controlled challenge However, there is no agreement on what would constitute a proper gluten challenge, as modalities and amount of gluten used.

Clearly, there is an urgent need to standardize a diagnostic protocol for clinical trials. In clinical practice, the diagnosis is almost invariably made on the patient’s report and often even without having properly excluded CD. This practice represents a major obstacle toward progress in understanding this entity.

Wheat Allergy

It is possible that at least a subset of NCGS patients may have a non-IgE-mediated food allergy. Studies have shown that about one-third of IBS patients improved on an elimination diet and worsened on a DBPC challenge with wheat and cow’s milk proteins, suggesting that a percentage of them could be suffering from non-IgE-mediated food allergy. The majority of these patients studied showed lymphocytic enteritis in the duodenal mucosa.

Early-stage Celiac Disease

While the diagnosis of celiac disease follows a well standardized process and is clearly defined, there are instances in its early development where the disease cannot yet be detected either by serum antibody testing or by pathology. Yet, culture supernatants from duodenal biopsies or tissue sections of duodenal biopsies may be able to detect the highly specific autoantibodies in patients who are symptomatic but have normal histology and negative serum markers for CD. Thus, a portion of patients labeled with NCGS may indeed be seronegative celiac patients still lacking overt intestinal damage.

A Placebo/Nocebo effect

The profound effect of placebo is well recognized in a variety of functional gastrointestinal disorders, and even in organic and severe conditions such as Crohn’s disease, where about 15% of patients experience improvement on placebo. The existence of a relevant phenomenon of placebo/Nocebo effect has in fact been reported in double-blind controlled trials in adult patients with self-reported food intolerances and the likelihood of a placebo effect of gluten withdrawal has been suggested.

In a study on patients with IBS-like symptoms claiming to suffer from various food intolerances, only 12 of the 32 (37.5%) patients self-reporting such symptoms improved on an elimination diet and reacted to the DBPC challenges, indicating that almost 2/3 of such patients did indeed present a typical placebo/nocebo effect. Thus, it is quite conceivable that a portion of NCGS patients, and arguably a substantial one, fall in this category. Given the lack of any objective diagnostic marker, this appears quite likely.

Conclusions

Until more is known, it is questionable whether gluten is causing NCGS and whether NCGS involves an immune-mediated mechanism. In the absence of robust data, the term “sensitivity” should be replaced by the generic term “intolerance”. Thus, the misleading term “non-celiac gluten sensitivity” should be replaced with the term “wheat intolerance syndrome,” to reflect the causative role of wheat (rather than gluten) as well as the lack of a specific underlying mechanism, and potential for multiple causes of symptoms.

At some point, when research will tease out the various components of wheat intolerance syndrome and clarify its pathogenesis, medicine will abandon this umbrella term for more specific ones, much like the evolution for the syndrome of “intractable diarrhea of infancy” of the 70’s, another term that over time was abandoned as new entities were being uncovered: microvillus inclusion disease, milk protein enteropathy, immune deficiencies, and others.

Until then, let’s all humbly take a step back: Change the terminology to one that makes sense, stop making diagnostic algorithms as if we were dealing with a single entity, and go back to the drawing board to design rigorous prospective, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled, studies with a well standardized approach to answer the many outstanding questions.”

REFERENCES

- Ellis A, Linaker BD. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity? Lancet. 1978;1(8078):1358-9.

- FODMAPS (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols)(15) are a series of carbohydrates that are suspected as the culprit in many IBS-like symptoms. In fact, evidence is pointing at FODMAP foods, so much so that eliminating “gluten” in practical terms may mean eliminating FODMAP, as wheat, rye and barley-derived products carry the highest FODMAP content. Of course, it is unlikely that all NCGS subjects are FODMAP-sensitive, as this condition could hardly explain the occurrence of extraintestinal manifestations such as depression(16)2).

- Volta U, Bardella MT, Calabro A, Troncone R, Corazza GR, Study Group for NonCeliac Gluten S. An Italian prospective multicenter survey on patients suspected of having non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMC medicine. 2014;12:85.

- Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Haines M, Doecke JD, et al. Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2011;106(3):508-14; quiz 15.

- Francavilla R, Cristofori F, Castellaneta S, Polloni C, Albano V, Dellatte S, et al. Clinical, serologic, and histologic features of gluten sensitivity in children. The Journal of pediatrics. 2014;164(3):463-7 e1.

- Bruni O, Dosi C, Luchetti A, Della Corte M, Riccioni A, Battaglia D, et al. An unusual case of drug-resistant epilepsy in a child with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Seizure : the journal of the British Epilepsy Association. 2014;23(8)674-6.