Myth Busted – Modern Wheat Not to Blame!

Is modern wheat responsible for increases in the rates of celiac disease and non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivities? This registered dietitian says no!

Is modern wheat responsible for increases in the rates of celiac disease and non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivities? This registered dietitian says no!

- Carrie Dennett, M.P.H., R.D.N., Environmental Nutrition Newsletter 1

Bread’s reputation has taken a hit from the low-carbohydrate and gluten-free trends. Despite its long and revered history, today many people feel virtuous when they avoid the bread basket — or guilty when they eat toast.

Wheat is one of the most nutrient-rich foods on the planet, but modern wheat breeding has robbed us of that nutrition.

Is modern wheat also responsible for increases in the rates of celiac disease and non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivities? Here’s a look at the facts — and the myths.

The Gluten Myth

Einkorn and emmer are ancient wheats, while common wheat, which is about 9,000 years old, is the result of hybridization between emmer and wild “goat grass.”

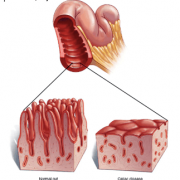

Common wheat, which contains the genes most likely to play a role in celiac disease, includes both heritage (or heirloom) wheats — genetically diverse, regional varieties — and modern “commodity” or “industrial” wheat.

Modern wheat debuted in the 1950s and is primarily grown on large farms in the western and plains states. It scores high marks for uniformity and high yield in ideal environments, but it doesn’t prioritize taste or nutrition.

- Wheat contains many groups of proteins that could potentially cause immune reactions such as allergies or celiac disease. The gluten group of proteins includes glutenins and gliadans.

It’s the gliadins that are more likely to trigger celiac disease and some types of wheat allergy.

It’s the gliadins that are more likely to trigger celiac disease and some types of wheat allergy.

- However, modern wheat ISN’T higher in gliadins; it has been bred to encourage glutenins, because they’re essential for bread baking quality, says Lisa Kissing Kucek, PhD, a plant research geneticist for the United States Department of Agriculture.

”Modern wheat breeders have been very good at increasing the types of glutenins that make good bread,” Kucek says. She says there is a very tiny difference between modern and heritage wheat for most sensitivities, especially celiac and wheat allergies. “Depending on what type of sensitivity people have, heritage wheats are not going to be the answer most of the time.”

Kucek says a larger issue is how wheat is processed — from farm to mill to bakery. For example, heavy use of nitrogen fertilizers leads to higher protein content overall, but it also specifically boosts gluten — and gliadins. That’s compounded by the fact that traditional methods like sprouting and fermenting — both of which can break down difficult-to-digest proteins — are largely missing from “industrial” bread baking.

Modern Breadmaking

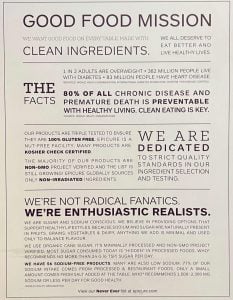

How did we get from hand-formed rustic bread made from four ingredients — whole wheat flour, water, salt and maybe yeast — to squishy plastic-wrapped bread with more than 25 ingredients? One reason is that industrial baking needs standardized flour that works predictably at large volumes in mechanized assembly lines. In other words, white flour with high protein content and low mineral content.

Unfortunately, white flour has fewer enzymes available to help break down the gluten, because most of those enzymes were in the bran. And even artisan bakers use mostly white flour, because wheat bred for white flour and industrial baking doesn’t work for whole wheat bread and natural fermentation — the dough isn’t strong enough to carry the bran and the germ.

”Whole grain bread started becoming more popular in the 1970s, but people didn’t want dense bread, they wanted their fluffy bread,” Kucek says. “The thing is with whole grain, you have the bran, and that bran can act like little razor blades.” This disrupts gluten development and loaf volume. “It’s tough to get the fluffy bread that people are used to for their sandwiches.”

- Industrial bakers found a work-around, but perhaps at some cost to health — instead of nurturing the dough, they started adding extra gluten to bread to achieve the texture that consumers expect.

Visit the bread aisle in any grocery store and start picking up loaves of whole grain bread. On the ingredient list you’ll see “wheat gluten” or “vital wheat gluten” — gluten that’s been isolated from wheat flour — even from brands perceived to be more healthful.

- Vital gluten intake may have tripled since the late 1970s, and consuming isolated gluten could create problems for some individuals.

“There are enzymes within the wheat kernel that are important for helping us break down a number of compounds in wheat,” Kucek says.

- “When we artificially separate the gluten and add it after the fact, we don’t have these enzymes to help us process that.”

If you don’t have celiac disease but have a family history of it, Kucek recommends avoiding breads that contain vital wheat gluten, seeking out alternatives that use sprouted grains and have had a long fermentation.

Future science

Kucek says there’s a wave of innovation in “post-modern” wheat breeding, which includes looking for favorable genetic traits in heritage wheats that might be adapted and improved, including nutrition, flavor, disease resistance, yield, and even reduced risk of provoking an immune response. This may also make it easier and more affordable for bakers to create slow-fermented, fluffy whole wheat bread — no added gluten needed.

“There can be a lot of nostalgic excitement about those old varieties, and they do serve a huge purpose in terms of biodiversity and flavor, but we’ve moved on from that,” she says.

Environmental Nutrition is the award-winning independent newsletter written by nutrition experts dedicated to providing readers up-to-date, accurate information about health and nutrition.