What Doctors Need to Know About Celiac Disease

An estimated 1% of the global population has celiac disease, but up to six out of seven patients with the condition are undiagnosed, according to a study published in the American Journal of Medicine.

An estimated 1% of the global population has celiac disease, but up to six out of seven patients with the condition are undiagnosed, according to a study published in the American Journal of Medicine.

- Alaina Tedesco, healio.com 1

Healio Internal Medicine spoke with Hilary Jericho, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and the director of pediatric clinical trial research at the University of Chicago Medicine Celiac Disease Center, to unravel the complex causes of celiac disease and related symptoms that patients may exhibit. She also offered advice to primary care physicians on how to diagnose, manage and treat the disease.

Q: Many individuals with celiac disease are undiagnosed, what are some signs of the disease primary care physicians should be aware of?

A: The problem with celiac disease is it’s one of the most diversely presenting conditions out there. The classic signs of celiac disease are gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea and abdominal pain. Many patients with celiac disease have excess gas and bloating of their abdomens, while some have nausea or vomiting when they ingest gluten.

Poor weight gain and short stature may also be indicative of celiac disease. A patient can have atypical symptoms of celiac disease which are thought to be related to nutrient malabsorption.

In children, dental enamel hypoplasia — a condition where the dental enamel didn’t form well because it’s not absorbing the right nutrients — could also signal celiac disease.

- Basically, just about any condition from joint pains to headaches to seizures to loss of hair can be symptoms of celiac disease. As if that isn’t complicated enough, a patient can be 100% asymptomatic and have celiac disease.

Physicians can identify asymptomatic patients by regularly screening “high-risk patients” or those who are first-degree relatives of patients with celiac disease.

There’s a subset of diseases that share genes with celiac disease. Type 1 diabetes is a significant one and patients with the condition should be routinely screened even if they are asymptomatic. There are a handful of others, including Down syndrome and multiple sclerosis. There are no set screening protocols in those populations, but physicians should be more vigilant in such patients.

- Physicians should not screen everyone for celiac disease, but they should have to have a very low threshold for looking for it. If a patient’s repeatedly complaining about something and the standard causes are coming up normal, then physicians must think about it.

Another significant correlation that we’re seeing more often is infertility in women. Physicians should consider testing for celiac disease in women who are having repeated miscarriages or difficulty getting pregnant and no other causes are likely.

Celiac disease can cause so many different things, so it’s hard to outline a set of very specific symptoms physicians need to look for. Physicians just need to be aware it’s becoming more and more prevalent and that patients can present with very different symptoms.

Q: How can primary care physicians manage and treat symptoms of celiac disease in their patients?

A: The test we use to screen for celiac disease is tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA) because it’s inexpensive and the most sensitive and specific. About 3% to 4% of patients have immunoglobin A (IgA) deficiency, so physicians should always send the two tests together to make sure the testing’s reliable.

- If the patient’s tTG-IgA and IgA screening labs come back abnormal, the patient should see a gastroenterologist for the next steps.

The gastroenterologist may order additional blood tests that are more specific or an upper endoscopy to take tissue samples from the duodenum, which will confirm that they have celiac disease. If celiac disease is confirmed, physicians should start patients on a strict, gluten-free diet which is the only treatment for celiac disease.

However, physicians should be aware that the tTG-IgA test may include false positives.

- The last thing a physician should do if a patient comes back with an elevated tTG-IgA is put them on a gluten-free diet. If the diet helps them feel better, the patient isn’t going to want to come off and now they’re committed to a lifelong gluten-free diet and there hasn’t been an established diagnosis.

Q: What is the bottom line for caring for patients with celiac disease in primary care?

A: It’s a lot to ask of primary care doctors to screen, diagnose and treat celiac disease because there are a lot of minute details related to the disease.

Primary care physicians should know that the diet is serious and the repercussions of poor adherence are serious. It’s critical that patients follow the diet correctly and that they adhere to it. While the gluten-free diet can be nutritious if done correctly — sticking to a lot of whole grains, fruits, vegetables, meats and avoiding too many processed gluten-free foods — it can be very unhealthy if it isn’t done in the right way and it’s not a balanced diet.

Families often include too many processed foods which are high in concentrated fat and sugar. It’s important that a newly diagnosed celiac patient talks to a trained nutritionist or dietitian who is well versed in the gluten-free diet and ensures that the patient is following the diet in healthy way which isn’t going to lead to nutrient deficiencies.

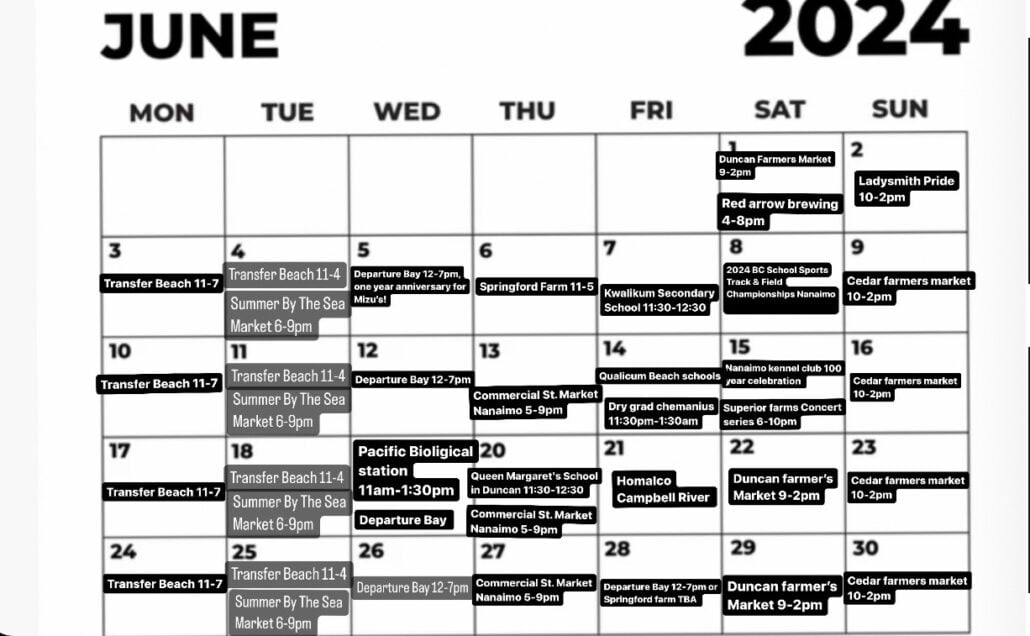

Eating out can be difficult because of the increased potential for contamination and accidental ingestions of gluten. Therefore, physicians should recommend that patients limit eating out because it’s often a big area of contamination. If there’s any concerns the diet isn’t being followed or a patient needs guidance, collaboration with a well-trained dietitian to review the diet and try to pinpoint areas that are leading to possible contamination is important.

Background Information: What are the underlying causes of celiac disease?

Answer: No one perfectly understands what sets the ball rolling. Celiac disease can occur anywhere in someone’s life from the very first time they eat gluten, which is typically around 6 months of age, to upwards of 90 years of age.

There are a couple things that need to exist for celiac disease to develop. First, you must have the genes for celiac disease which are DQ2and DQ8.

Risk profiles for developing celiac disease vary depending on which genes a patient has. Having both copies of the DQ2 genes is associated with the highest risk, but even people who only have one half of that DQ8 can still develop celiac disease.

Second, you must have exposure to gluten which is found in three grains: wheat, rye and barley. If you take gluten out of the diet of a person with active celiac disease, everything should heal — any abnormalities, symptoms, lab findings or anything else related to active celiac disease should normalize.

Multiple studies show that somewhere from about 30% to 40% of the population have the gene for celiac disease, but only 1% of the population actually goes on to develop celiac disease. The question is, why does it only occur in 1% of those people with the genes? It’s thought that some sort of environmental trigger sets the ball rolling in these patients who are eating gluten and have that genetic predisposition.

Researchers have looked at many potential triggers, from antibiotic exposure to infections to when and how gluten is introduced. However, there’s no clear-cut evidence indicating what causes some people to develop celiac and not others currently.

If a patient has the genes, is eating gluten and one of these environmental factors occurs, the normal bacteria in their gut will be disrupted and a more pro-inflammatory composition will be favored. The gut then becomes leaky and gluten crosses the lining leading to an inflammatory response instead of our normal tolerogenic response (absorption and processing of gluten for nutrients and energy without inflammation).

The inflammatory pathway triggers our immune system to respond negatively to gluten. The production of inflammatory cells and T cells lead to this infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lining of the first part of the intestinal tract, the duodenum and blunting of the villi responsible for absorption. This ultimately leads to nutrient malabsorption and symptoms such as cramping, diarrhea, and poor weight and height growth.

Nutrient malabsorption within the duodenum can also lead to other repercussions such as iron deficiency anemia, thinning of bones and calcium and vitamin D malabsorption.

Reference: Paez MA, et al. Am J Med. 2017;doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.05.027.

Disclosure: Jericho reports no relevant financial disclosures.