Better Adherence to Gluten-Free Diet Improves Mucosal Recovery in Celiac Disease

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) – Individuals with celiac disease who follow their gluten-free diet more closely are more likely to show complete mucosal recovery one year after diagnosis, researchers from Finland report.

Although most patients with celiac disease eventually achieve complete mucosal recovery with a strict gluten-free diet, a significant proportion has not reached complete mucosal healing at one year.

As a first step to being able to distinguish patients with a slow histological response from those with true refractory celiac disease, Dr. Kalle Kurppa’s team from the University of Tampere and Tampere University Hospital, sought to identify patient-related factors that might predict incomplete histological recovery at follow-up biopsy one year after diagnosis in their study of 263 adults with biopsy-proven celiac disease.

After one year on a gluten-free diet, 68% of patients showed normalized small-bowel mucosal morphology and constitute the recovery group. The other 32% with incomplete mucosal recovery constitute the atrophy group.

Patients in the atrophy group had significantly more malabsorption, significantly higher serum levels of transglutaminase-2 antibodies, and significantly more severe small-bowel mucosal damage at diagnosis than patients in the recovery group, according to the June 2 online report in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Only 13% of patients in both groups reported dietary lapses, but low adherence to the diet predisposed patients to incomplete mucosal recovery in the follow-up biopsy.

Despite the differences in mucosal recovery, the recovery and atrophy groups did not differ at diagnosis or at one year in the degree of gastrointestinal symptoms or health-related quality of life.

Malabsorption at diagnosis was the only factor in multivariate analysis significantly associated with an increased risk of incomplete villous recovery at one year.

Long-term follow-up data revealed no significant differences between the atrophy and recovery groups in the rates of mortality, malignancies, or other complications and comorbidities.

“Based on these findings a more personalized approach should be adopted when deciding the optimal timing of the histological follow-up,” the researchers concluded. “One year is often too short a time for the mucosa to recover, and postponing the biopsy, e.g., for another year, would presumably result in lower number of cases with ongoing atrophy.”

“There is some controversy and uncertainty about whether every adult with celiac disease should have a follow-up biopsy, and when to do so,” Dr. Lebwohl said. “Because so many people have persistent damage at one year that just represents gradual healing, I and several of my colleagues usually advise repeating the biopsy at two years.”

“We know from previous studies that ongoing intestinal damage increases the risk of lymphoma and certain fractures,” Dr. Lebwohl said. “While we’re still learning about the role of the follow-up biopsy and its optimal timing, it is important to see this in the context of our ultimate goal for patients with celiac disease, which is to reduce the risk of complications and maximize longevity and quality of life. Most patients heal on follow-up, and some of those who do not heal initially will eventually do so. The follow-up biopsy is one of several tools we have to monitor adherence to the gluten-free diet and to predict outcomes.”

“However, this study indicates to clinicians that, regardless of dietary adherence, mucosal recovery is unlikely to be attainable in all patients at one year and that clinicians need to interpret the degree of change in the follow-up biopsies in the light of the severity of the mucosal damage at diagnosis,” Dr. Woodward said.

“Whilst it is possible (although not proven in this study) that delaying the follow-up biopsy to 18 months or two years may increase the proportion of patients who demonstrate mucosal recovery, this may not be the only consideration for the timing of the repeat examination,” he added.

SOURCE: Am J Gastroenterol 2015. https://www.nature.com/ajg/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ajg2015155a.html

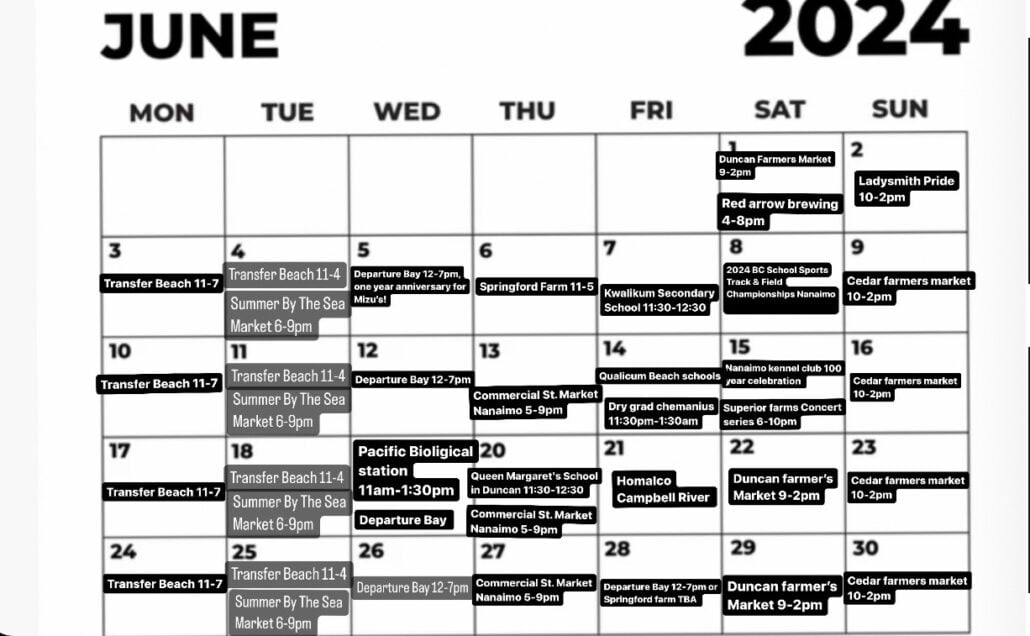

Brentwood Bay, Campbell River, Chemainus, Cobble Hill, Colwood, Comox, Coombs, Courtenay, Cortes Island, Cowichan Bay, Deep Cove, Duncan, Errington, Esquimalt, Gabriola Island, Hornby Island, Ladysmith, Lake Cowichan, Langford, Metchosin, Mill Bay,Nanaimo, Nanoose Bay, Parksville, Port Renfrew, Salt Spring Island Shawnigan Lake, Saanich, Sidney, Tofino and Ucluelet