Overlapping Symptoms of Celiac Disease, Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity, Irritable Bowel Syndrome and FODMAP Intolerance

September 7, 2015 – A review in Nutrition Journal seeks to shed light and tease apart the overlapping symptoms of celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, irritable bowel syndrome and FODMAP Intolerance in hopes of finding a way to separate them in everyday clinical practice.

September 7, 2015 – A review in Nutrition Journal seeks to shed light and tease apart the overlapping symptoms of celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, irritable bowel syndrome and FODMAP Intolerance in hopes of finding a way to separate them in everyday clinical practice.

The language in the report is dense if not heavy going despite efforts by The Celiac Scene to simplify. Those endeavoring to tease apart their own shifting sand of symptoms will find the effort worthwhile. The review underlines just how confusing matters still are – for both patient and doctor.

Nutrition Journal 2015, 14:92 doi:10.1186/s12937-015-0080-6

by Magdy El-Salhy, Jan Gunnar Hatlebakk, Odd Helge Gilja and Trygve Hausken

Introduction

Wheat products make a substantial contribution to the dietary intake of many people worldwide. Despite the many beneficial aspects of consuming wheat products, it is also responsible for several diseases such as Celiac Disease (CD), and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS).

Wheat products make a substantial contribution to the dietary intake of many people worldwide. Despite the many beneficial aspects of consuming wheat products, it is also responsible for several diseases such as Celiac Disease (CD), and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS).

CD is an immunological response to ingested gluten that results in small-intestine villous atrophy with increased intestinal permeability and malabsorption of nutrients

NCGS is characterized by both gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal symptoms that are triggered by the ingestion of wheat products (possibly due to the gluten content). These symptoms improve after removing wheat products from the diet, and relapse following a wheat challenge. NCGS is often perceived by the patients themselves, leading to self-diagnosis and self-treatment.

Patients with CD, NCGS and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) exhibit similar gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal symptoms: abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, nausea, and vomiting, and the extragastrointestinal symptoms are headache, musculoskeletal pain, brain fog, fatigue, and depression.

The Suggestion of an Overlap

CD and IBS patients have similar gastrointestinal symptoms, which can result in CD patients being misdiagnosed as having IBS. Therefore, CD should be excluded in IBS patients.

CD and IBS patients have similar gastrointestinal symptoms, which can result in CD patients being misdiagnosed as having IBS. Therefore, CD should be excluded in IBS patients.- A considerable proportion of CD patients suffer from IBS symptoms despite adherence to a gluten-free diet (GFD).

- The inflammation caused by gluten intake may not completely subside in some CD patients.

- It is not clear that gluten triggers the symptoms in NCGS, but there is compelling evidence that carbohydrates (fructans and galactans) in wheat does.

- It is likely that NCGS patients are a group of self-diagnosed IBS patients who self-treat by adhering to a GFD.

The Connection Between IBS and CD: A Misdiagnosis or an Overlap?

There is overlap in the symptoms of IBS and CD and since the diagnosis of IBS is based mainly on symptom assessment, there is a risk of CD patients being misdiagnosed as having IBS.

There is overlap in the symptoms of IBS and CD and since the diagnosis of IBS is based mainly on symptom assessment, there is a risk of CD patients being misdiagnosed as having IBS.

The situation is complicated even further by the fact that the abdominal symptoms in both IBS and CD patients are triggered by the ingestion of wheat products. However, whereas this is caused by gluten allergy in CD patients, it is attributed in IBS patients to the long-sugar-polymer fructans in wheat.

The prevalence of CD patients among IBS patients who have been misdiagnosed using symptom criteria for IBS lie in the range 0.4–4.7 %. Regardless of this variation in the prevalence of CD patients who have been misdiagnosed with IBS between studies, it is a considerable number that should not be disregarded.

These findings have led to the British Society of Gastroenterology recommending that CD should be excluded in all patients referred with IBS. The American College of Gastroenterology have advised the exclusion of CD in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS and IBS with a mixed bowel pattern. We believe that all referred IBS patients should be tested for CD with serologic testing. When there is doubt, duodenal biopsy samples should be taken. Patients with CD who were initially diagnosed as having IBS face a diagnosis delay of 10 years as compared 7 years, the delay that CD patients experience without receiving an initial diagnosis of IBS.

Patients with Both CD and IBS

It is not uncommon for patients with CD who consume a gluten-free diet (GFD) and suffer from IBS symptoms to present at the clinic. Reportedly 20–23.3 % of treated CD patients fulfill the symptom-based criteria for IBS. Despite adhering to a GFD, patients with CD who exhibit IBS symptoms have a reduced quality of life as compared with those who do not. It is possible that CD and IBS coexist in some patients, however, it is more likely that the inflammation in CD does not subside completely in some patients after implementation of a GFD, and a low-grade inflammation may exist.

NCGS

NCGS receives widespread interest from the general public and mass media, and is often confused with the popular assumptions and speculations that the high carbohydrate content of wheat is responsible for negative health aspects such as obesity. The situation is exacerbated by celebrities propagating these speculations as a means of losing weight. The concept of NCGS was first introduced in 1978 with a case report of a patient with abdominal pain and diarrhea who exhibited no abnormalities on small-intestine biopsy samples, whose symptoms improved when they changed to a GFD.

A study of eight adult females with abdominal pain, diarrhea, and small-intestine biopsy findings with no significant changes published in 1980 found that symptoms were relieved when the patients adhered to a GFD, and returned after a gluten challenge. Similar results have been reported in patients with nonceliac IBS-like symptoms. The withdrawal of wheat products was found to improve these symptoms in double-blind randomized, placebo-controlled studies involving patients with IBS-like symptoms.

Is Gluten Responsible for NCGS? Could it be FODMAP Intolerance?

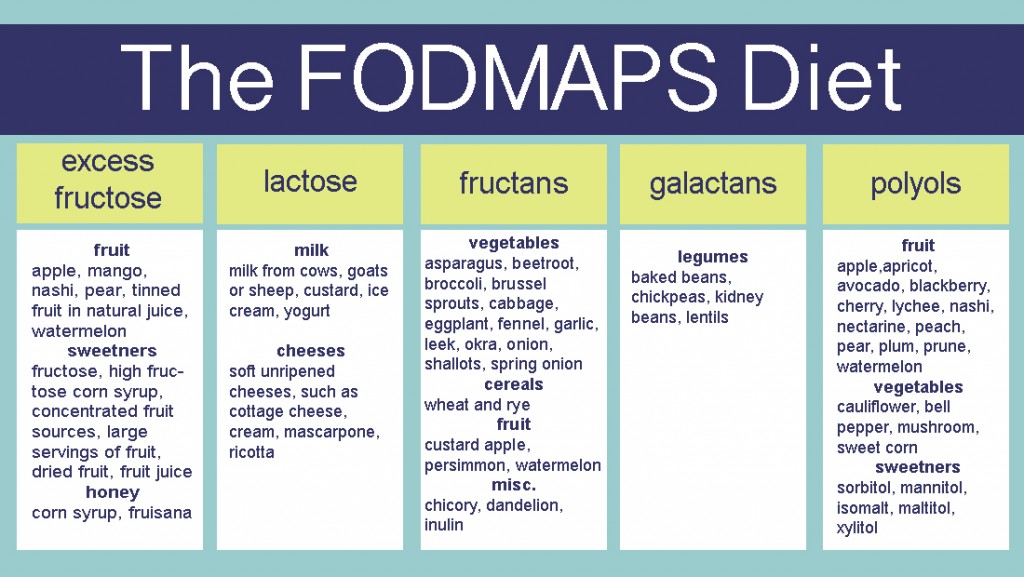

Studies indicate that it is not clear that gluten is responsible for triggering NCGS symptoms; instead, it appears that it is the carbohydrate content (fructans and galactans) in the wheat that triggers these symptoms. Indigestible and poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates with chains containing up to ten sugars (which are collectively called FODMAPs) occur in a wide range of foods, including wheat, rye, vegetables, fruits, and legumes. These carbohydrates exert osmotic effects in the large intestinal lumen, resulting in an increased water content. They are also fermented rapidly by intestinal bacteria, with consequent gas production.

Several studies, including some randomized, placebo-controlled studies, have shown that FODMAPS trigger gastrointestinal symptoms in IBS, and that a low-FODMAPs diet reduces symptom severity and improves the patient’s quality of life. Read more about FODMAPs here.

It is noteworthy that initiation of GFD without dietetic supervision or education can cause inadequacies of nutrient intake including fiber, thiamin, folate, vitamin A, magnesium, iron, and calcium. Furthermore, it is difficult and more expensive to follow a GFD.

Connection Between IBS and NCGS

The definition of NCGS coincides with that of IBS: they have the same gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal symptoms. A point of difference may be that NCGS patients’ symptoms improve on withdrawal of gluten and return with gluten ingestion. However, it is not clear that gluten triggers the symptoms in NCGS patients; rather, there is compelling evidence that they are triggered by the fructan and galactan carbohydrate components, which are FODMAPs.

Furthermore, a considerable number of patients with NCGS experience no improvement of symptoms despite consuming a GFD, and a large number appear to avoid other food items that contain high levels of FODMAPs in addition to consuming a GFD.

The fructan contents in gluten-free bread (mostly made of rice/corn), bread made from white wheat flour, and bread made from spelt flour are 0.19 g/100 g, 0.68 g/100 g, and 0.14 g/100 g, respectively. In addition, spelt flour contains 16 % less protein (mostly gluten) compared to wheat.

Given the likelihood that it is the carbohydrate components of wheat that trigger symptoms in NCGS, spelt products would be a better alternative to wheat than a GFD, which is widely used by IBS patients.

The following statements from the research groups of Murray and Sanders should be emphasized in the ongoing debate regarding NCGS:

“Symptoms, symptom complexes, and symptom characteristics are rarely, if ever diagnostic”

“We believe that further work is required in what we perceive as the research fertile crescent of gluten sensitivity! Only then can we better inform practicing clinicians on how to manage this group of patients.”

Conclusions

- CD patients experience gastrointestinal symptoms similar to those seen in IBS patients, and are thus at risk of being misdiagnosed as having IBS, contributing to a further delay in diagnosis. Therefore, CD should be excluded in IBS patients, regardless of the subtype.

- A considerable proportion (20–37 %) of CD patients suffer from IBS symptoms despite adherence to a GFD.

- It is likely that the inflammation caused by gluten intake does not completely subside in some CD patients, similar to what is seen in inflammatory bowel diseases, whereby a considerable number of patients exhibit IBS symptoms in the remission phase.

- It is not clear that gluten triggers the symptoms in NCGS, but there is compelling evidence that carbohydrates (fructans and galactans) in the wheat does.

- Patients with NCGS exhibit the same gastrointestinal and extragastrointestinal symptoms as those with IBS. Withdrawal of wheat products reduces the symptom severity and improves the quality of life in both NCGS and IBS patients.

- Furthermore, there are no specific blood tests or radiological or endoscopic examinations that are diagnostic for either NCGS or IBS. It is likely that NCGS patients constitute a group of IBS patients who are self-diagnosed and have self-treated by adhering to a GFD.

********

The Celiac Scene has removed footnotes and simplified the language for ease of understanding. The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at: https://www.nutritionj.com/content/14/1/92 © 2015 El-Salhy et al

********

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.