Gluten-Free Craze a ‘Double-Edged Sword’ for Celiac Patients

The gluten-free diet craze is both reassuring and upsetting to people with celiac disease who are allergic to the nutrient, a small study suggests.

The gluten-free diet craze is both reassuring and upsetting to people with celiac disease who are allergic to the nutrient, a small study suggests.

- Maureen Salamon, HealthDay Reporter 1

People with celiac disease say they’re happy to have more food choices at stores and restaurants. But some with celiac sense a growing stigma as other people voluntarily go gluten-free. And many patients fear people see them as “high-maintenance” and misunderstand the severity of their disease.

“On the one hand, you have a lot more options available for patients that taste better and are becoming more affordable. But at the same time, you have this gluten-free craze that’s recognized as kind of a fad diet, so celiac disease goes misunderstood in social situations, leaving patients more anxious,” said study author James King.

He’s a graduate student in the department of community health services at the University of Calgary, in Canada.

Learn more about the Canadian Celiac Association’s support of this study.

Celiac is an inherited autoimmune disorder affecting about 1 percent of people in North America. When those who have it consume gluten — a protein found in wheat, rye and barley — their immune system reacts by attacking the small intestine.

And, according to the Celiac Disease Foundation, the disorder has been tied to other serious health problems, including cancer and type 1 diabetes. Avoiding gluten is the only current treatment.

Meanwhile, a gluten-free diet has become a trendy choice for many without celiac disease, either to shed pounds or for other purported health benefits. Some embrace it due to a sensitivity to gluten that creates unpleasant, but not damaging, gastrointestinal symptoms.

For the study, King’s team interviewed 17 celiac disease patients about their experiences in an evolving gluten-free world.

“Just having a prescription of a gluten-free diet for people with celiac disease … doesn’t acknowledge some of the challenges patients face after treatment,” King said.

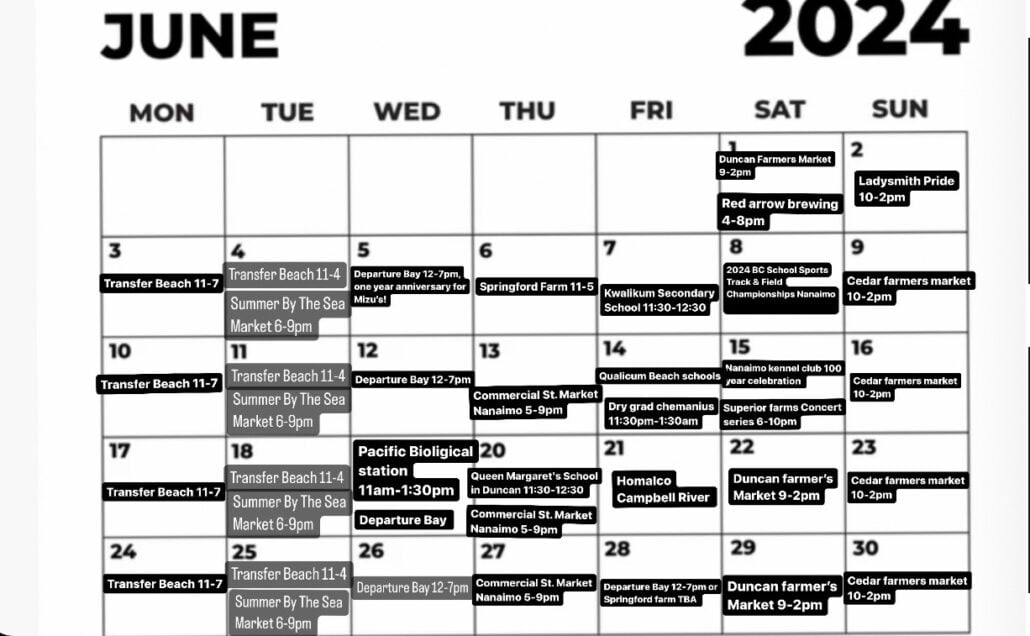

His team found, for example, that participants were fearful of inadvertently consuming gluten when they eat out. That’s because restaurants may say they are “gluten-free friendly,” but not do enough to avoid cross-contaminating foods. After all, King said, many of their customers simply prefer gluten-free, but they don’t require it.

“Some participants discussed how they sometimes feel high-maintenance or difficult by asking how food is prepared,” he said. “They felt a lot of restaurants nowadays have embraced this business opportunity to have gluten-free options … but are unsure how strict they’re going to be to make it gluten-free.”

Marilyn Geller is chief executive officer of the Celiac Disease Foundation in California and wasn’t involved in the new research. She said the findings reinforce what celiac patients typically report.

“Overwhelmingly, they feel socially stigmatized because of the disease,” she said. “With the push to a gluten-free diet, the disease is no longer taken seriously. If you go into a restaurant now and the server hears you’re gluten-free … they often don’t consider it a medical condition.”

Geller said a drug treatment for celiac disease must be developed to impress its seriousness upon the public. Better training for restaurant workers also might help, she said, but not as much as a medication.

“The real drawback is because there’s not yet a medication — and in America, we equate medications with serious conditions — people are not going to take it seriously,” she said.

King suggested that health care providers point celiac patients to registered dieticians, local support groups and other resources that might help.

The study was published online recently in the Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics