My Mother’s Long & Winding Road to Diagnosis

Mom was born in 1933, in the city of Malang, Java, an island in the Dutch East Indies. She was the daughter of Dutch nationals who operated a sugar plantation in this most tropical setting.

Mom was born in 1933, in the city of Malang, Java, an island in the Dutch East Indies. She was the daughter of Dutch nationals who operated a sugar plantation in this most tropical setting.

While her mother bore the blonde, blue-eyed visage typical of the Dutch, her father was of Indonesian lineage. As a result, my mother had a beautifully exotic appearance that would ultimately capture my father’s heart.

Mom spent her childhood in the jungles of Sumatra. Her older brother was born with spina bifida . The immediate treatment offered in those days resulted in him being paralyzed from the waist down.

While her mother performed hours of physiotherapy with him indoors, Mom contented herself playing outdoors with the chickens, dressing them in dolls’ clothing.

Her idyllic childhood came to an abrupt end in 1942 when the Japanese invaded Indonesia. She, her mother and brother were interned at a Prisoner of War (POW) camp for three and a half years. Her father meanwhile, was enslaved by the Japanese army to work on the Burmese Railroad, under the most wretched of conditions. It was a miracle that he survived.

Growing up, mom ‘entertained’ us with stories about the POW camp, portraying them as seemingly carefree days where both the women and children could get into mischief. Like the night that they feasted on a crop of potatoes meant for harvesting and then trying to contain their giggles when the soldiers pulled up dead plants the next day. Despite the punishment meted out to them – twelve brutal hours in the hot tropical sun – mom spoke with forgiveness about the Japanese guards. They too were miserable, separated from their own families, in the same conditions that the prisoners endured.

Mom spoke fondly of the corn starch puddings she resorted to eating when food was scarce. Her mother would place a small spoonful of precious sugar in the centre of the bowl that mom could eat toward as a way to endure the glue-like texture.

Mom managed to maintain her weight throughout her internment, despite a diet of mainly potatoes and cornstarch. She emerged from her imprisonment at the same height and weight as when she arrived, little worse for wear. Others around her starved – some to death. It was when she repatriated to Holland and began eating a gluten-rich diet that she would become so thin that people would stop to stare.

Fast forward ten years to life in Canada as a new immigrant. The mother of a busy two year old, Mom began to show signs of Grave’s Disease and over the next 15 years, she would undergo one surgery, two treatments with radioactive iodine & hormone replacement therapy before her condition finally stabilized.

She enjoyed relatively good health until the age of 50, when she became insulin dependent, seemingly overnight. The condition is now recognized at Latent Autoimmune Diabetes of Adults (LADA). Autoimmune should have been a clue.

Mom made the best of her diabetes using the sounds of her blood sugar monitor to entertain her growing brood of grandchildren. As do many diabetics, Mom went on to develop atherosclerosis and underwent corrective bypass surgery of her carotid artery.

By age 55, mom began to experience strange bouts of diarrhea. They happened only when she dined at restaurants or at other people’s homes, never when she cooked her mostly Indonesian, rice-based diet. Her GP was convinced that that her preoccupation with her bowel functions was a manifestation of perio-menopause and gave her a prescription of valium. Naturally, the medication did nothing to resolve her digestive problems. She did however go on to experience something of a miracle.

She began to require less and less insulin to keep her blood sugars even. Her GP mused that perhaps she had made a a spontaneous recovery from diabetes.

The fact was that she had stopped absorbing nutrients altogether, likely due to her undiagnosed celiac disease. The subsequent electrolyte imbalance had her retaining fluid and her heart became dangerously congested as it coped with the fluids gathering in her legs and chest. We did not realize how close she came to death at that time.

It was at this point that she showed her GP an article written by Dr. Paul Donohue, a medical columnist in the Edmonton Journal. In it, Dr. Donohue described a malabsorption disorder with symptoms very similar to the ones Mom had been experiencing. The prescreening blood test did not exist at that time. To his credit, the doctor ordered an endoscopy and the biopsy was positive for celiac disease. Mom finally had her diagnosis., the result of her own investigative work. After a month in hospital, she returned home with her electrolytes balanced, her insulin readjusted and a life-long prescription for a gluten-free diet.

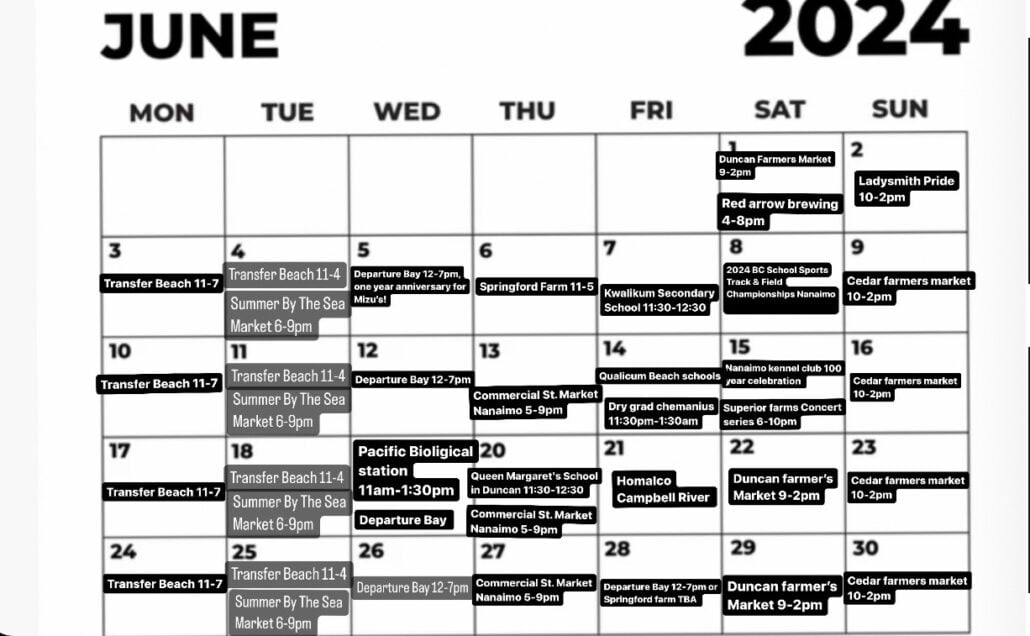

Mom and I attended her first support meeting together, hosted by the Edmonton Chapter of the Celiac Canada. Two Home Economics students studying for their Master’s Degree gave a presentation on methyl cellulose and how it could be used to bake gluten-free bread. The samples they offered us matched the gloom of that cold winter night in 1988!

Over time, mom would develop her own delicious, gluten-free recipes. Mom discovered that GF flours had a higher glycemic index than regular flours and that this wreaked havoc with her blood sugar. Her medical care team suggested she was being non-compliant to her diabetic diet.

She attended years of Chapter recipe exchanges and took great pride in the National Conference that the Edmonton Chapter hosted in 2006.

With her hyper-thryoidism, celiac disease and diabetic diagnoses finally addressed, our family had high hopes that this new lease on life would see her through to a ripe old age. However, it was not long before she developed yet another set of perplexing symptoms. She began to lose her balance while gardening and her movements slowed to a shuffle.

These symptoms and the presence of shimmering lights seen out of the corner of her eyes confounded a host of neurologists. She was alternately diagnosed with migraines (without the headache), Parkinson’s disease (without the tremor), Binswanger’s disease (a disease named in 1800’s) and something called transient ischemic attacks. Ataxia, due to white matter deposits in the brain became a running diagnosis.

Unfortunately, speculation came to an abrupt halt when she received an intervening diagnosis of oral cancer. Our family was stunned to learn that a person who never smoked or drank alcohol could be a candidate for this disease. Words cannot do justice to the suffering she endured after surgery and radiation.

My mother bore the pain and disfigurement with stoicism and to the surprise of her surgeon, reached the magical five-year mark, cancer-free. However, it was the inexorable progress of her confounding neurological disorder that would undermine this victory.

Slowly but surely, she was robbed of the mobility in her legs, then her hands until she finally became locked within a body that would no longer accept a single command. It was in this condition that my father assumed care of every need for two full years until she entered the hospital for the final time in December of 2010.

H. Yvonne Bayens could marvel at how many shades of green could be found in nature’s palette. She saw beauty in every flower; captured wild birds with her bare hands; could tease apart the tightest knot and calm the fussiest infant. She interpreted her world in clay, sculpting animals and children – always at play. She stepped ever-so-lightly on this earth but left an indelible imprint upon her family.

On December 9, 2010, my mother passed away at the age of 77, having endured a succession of belatedly diagnosed autoimmune disorder and a constellation of associated conditions.

Ellen Bayens